Here's a truth that many of us would rather ignore: Our brains still have some serious prehistoric programming going on.

We may no longer be dodging saber-toothed tigers, but our brains are still wired to respond to certain things in our environment.

The problem is, in today's world, many of those instincts are about as useful as a chocolate teapot.

They've morphed into what we call cognitive biases - little glitches in our thinking that can throw us off course without us even realizing it.

Now, psychologists have been studying this stuff for ages, and guess what?

Marketers caught on pretty quickly, too.

They've been sneaking these psychological techniques into their bag of tricks to sell us stuff we don't even need.

But wait - scientists aren't some brainiac robots immune to this stuff.

No, it turns out they're just as susceptible to these sneaky biases as the rest of us mere mortals.

So in this article, I'm going to spill the beans on eight of these mind-bending biases and how you can use them to sell your stuff to even the most skeptical lab coat-wearing types.

Let's dive in.

1. Anchoring effect

Have you ever heard of the anchoring effect?

It's a little trick our brains play on us where the first piece of information we get influences everything else that follows.

In one famous experiment, two groups of students were asked to guess at what age Mahatma Gandhi died.

But instead of an open-ended question, the two groups had an anchor to start with.

One group was asked whether Gandhi died before or after the age of 9, while the other group was asked the same question, but at the age of 140.

Of course, these two numbers are ridiculous and anyone could guess the answer, but here is the interesting effect of the anchoring bias: the first group's average answer was 50, while the second group's average answer was 67.

What does that tell you?

It's all about how you frame the question.

A common application of anchoring bias in marketing is to use an anchor on your price page.

An easy way to apply this effect is to simply cross out a higher price and place it next to the new price.

Amazon is an absolute master at this, and sometimes it feels like the entire store is on sale because every price is struck through.

They're asking $106 for this, and you're like, “That sounds expensive!”

But then you see the original price, almost double, and suddenly, that $106 feels like a steal.

Another easy way to use this on your pricing page is to offer a cheap option next to a much more expensive one.

You may not even be trying to sell the expensive stuff, because it's probably only going to appeal to a handful of people.

But just seeing that price gap?

It will make that lower-priced option look like a bargain.

2. Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is our brain's way of favoring information that confirms an existing belief.

That's why conspiracy theorists always find ways to confirm their wild theories, no matter how outlandish they sound.

We're wired to hear what we want to hear and conveniently dismiss the rest.

And don't think that scientists are above the fray-they're in the same boat.

In his book How Doctors Think, Jerome Groopman explains that doctors are constantly influenced by confirmation bias.

When making a diagnosis, a doctor automatically seeks to confirm the evidence rather than consider other alternative causes (this is also caused by the availability heuristic discovered by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky).

Even more disturbing is the fact that if a doctor has recently read a paper about a particular disorder, he will tend to diagnose that disorder more often than normal.

Now, let's bring this back to marketing and keep in mind that it's much easier to tap into what buyers already believe than it is to try to convince them of something new.

So one way to do this is to use social proof to confirm people's intuition about your product.

Let's say you're looking for a new sequencer for your lab because the one you already have is as bulky as a tank.

Odds are, you'll stumble upon Oxford Nanopore's site in your search for something sleeker.

And when you see those quotes from scientific papers praising their tech, well, it's like the universe is saying, "Yep, this is the answer you've been looking for."

Using client testimonials is a basic of copywriting, but through the confirmation bias, you can make sure that they are strategically placed to confirm the buyer’s intent and not just randomly placed on your website.

3. Framing effect

Now let's talk about the framing effect, which is a cognitive bias in which people make choices between options based on whether the options are presented with a positive or a negative connotation.

Take this example: you are faced with the choice of buying two different brands of yogurt.

One says “20% fat,” while the other says “80% fat-free.”

Which one will you choose?

I'll bet you lean toward the 80%, even though they have the same amount of fat.

This effect was demonstrated once again by the brilliant minds of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in a study published in 1981.

In this study, the psychologists asked participants to decide which treatment should be given to 600 people infected by a fatal disease.

Treatment A would save 200 people, but it would also kill 400.

Now, here's where it gets wild: When the researchers touted treatment A as “saving 200 people,” 72% of the participants were all in for using it.

But flip it to "killing 400 people,” and suddenly only 22% were on board.

In both cases, that’s the exact same number of deaths!

Our brains are simply unable to make a logical decision, because of the framing of the information.

So the secret to using this effect in your marketing is to position yourself with positive facts.

Would you trust this disinfectant cleaner if it was saying “Allows 0,1% of bacteria to survive”?

Apply this by turning every negative aspect of your product (and be honest, you have some) into its positive opposite.

So if your lab equipment has a 10% failure rate, spin it instead as a rock-solid 90% success rate.

It's all about framing your pitch in the best possible light (which, again, doesn’t change the fact that you have a 10% failure rate).

4. Authority bias

The authority bias is the idea that we put way too much trust in people we see as authority figures, and their recommendations can seriously influence our decisions.

The authority bias was brought to light by Yale University’s psychology professor Stanley Milgram in an infamous-and let's face it, kind of messed up-experiment.

In this study, participants were divided into two groups: teachers and learners.

The teachers were accompanied by a researcher (the authority figure) and they were tasked with quizzing the learners.

If a learner didn’t answer correctly, the teachers were instructed to press a button that would deliver an electric shock to the learner.

And here's the crazy part: the intensity of the shock increases with each wrong answer.

Now, no need to sweat, nobody was hurt because those learners were just actors putting on a show.

But here’s the weird thing: 65% of the teachers kept increasing the voltage, just because the researcher told them to.

Scientists are subject to the authority bias all the time.

Ever wondered why Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs) are so prized in science?

Well, if you are a top researcher in your field and you happen to recommend a particular brand, chances are that many of your peers will follow your advice.

This could also lead to malevolent use of authority bias, such as what Purdue Pharma did to promote its OxyContin drug, which led to the opioid crisis in the US.

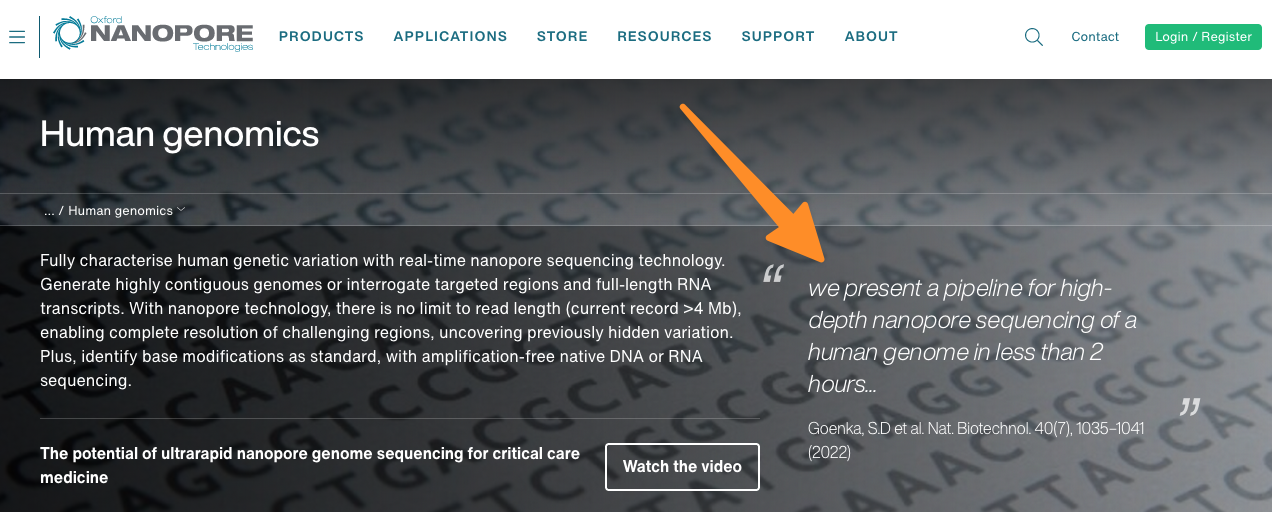

Purdue based all its addiction data on this 1980 letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine:

Because of this letter-which was so scientifically biased that it couldn't even be published as a real study-doctors were led to believe that “less than 1% of patients become addicted” (which, of course, is completely false and is, in reality, closer to 30%).

Instead of being evil like Purdue’s team, think about how you can collaborate with top-level scientists who are genuinely interested in your product.

Invite them to talk about it in a webinar, for example, and share their best practices with your audience.

These authority figures will be your best brand ambassadors, as long as your product is good enough to convince them.

5. Bandwagon effect

The bandwagon effect is the reason why we humans are more likely to jump on a decision just because everyone else is doing the same thing.

It's why a long line at a restaurant attracts even more people.

If they are willing to wait an hour for a sandwich, you want to get in on the action.

The bandwagon effect has mostly been studied in a political context, because it's thought to strongly influence voters' choices.

In a study published in 2017, German researchers decided to study this effect on 765 person.

Participants were asked to read newspaper articles about a fictitious municipal election that was supposed to take place in a small German town.

They were also given information about the candidates' backgrounds.

The participants were then divided into three groups, each of which received different polling results: some showing a clear winner, some showing a loser, and the last group receiving no polling results.

These poll results greatly influenced the participants' predictions.

The two groups that received the polls followed the poll result when asked who would win, regardless of the rest of the information they received.

But the people who didn't get the polling information based their choices on the candidates' track records instead.

Knowing that people are going to vote for someone influences our decisions.

Now, in the biotech world, we've got our own bandwagon shenanigans going down every January at the J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference.

This is an invitation-only event reserved for the most hyped biotech companies.

Despite its private nature, this event draws over 20,000 people to San Francisco each year, contributing over $86 million to the city’s economy in hotel rooms, private transportation and venue rental.

All of this is due to satellite events being organized around the official J.P.Morgan conference, just because all the big guns are in town.

Here’s how J.P.Morgan put it more politely on its website:

A simple way to exploit the bandwagon effect is to create a sense of scarcity.

If your favorite pastry shop sells out by 11 a.m. every Saturday, I’m sure you’ll be there first thing in the morning.

The same goes for your own product.

Sometimes it may be wiser to voluntarily create a limited supply, setting up the expectation that it will sell out in a short time.

Or, if you are organizing an event, offer a limited number of seats to attract the crowd more quickly.

6. Loss aversion

Our brains are wired to feel the pain of losing way more than the joy of gaining.

Picture this: You stumble upon a $20 bill lying on the sidewalk.

How do you feel?

Pretty good, right?

But now, flip the script-imagine losing that same $20 bill.

Suddenly, It's like your world collapses in despair.

According to none other than Kahneman and Tversky (yes, those two are like the rock stars of behavioral science), that feeling of loss hits twice as hard as the joy of finding that money.

In another study conducted in 1979, Kahneman and Tversky gave participants a choice between these two options:

- Option A: winning $1,500 with a probability of 33%, $1,400 with a probability of 66%, and $0 with a probability of 1%

- Option B: a guaranteed $920.

Guess which option participants chose the most.

Option B, even though option A is much more attractive given the very small chance of not winning (only 1%).

This shows how our brains are wired to avoid loss rather than objectively consider risk.

You can use this same mechanism in your marketing, especially to retain customers.

That’s what Amazon does when you try to cancel your Amazon Prime subscription.

Before you confirm, Amazon shows you the amount of shipping fees you've saved thanks to Prime (and it's often much more than the annual cost of the subscription).

So instead of canceling, you happily keep it and convince yourself that you got a good deal.

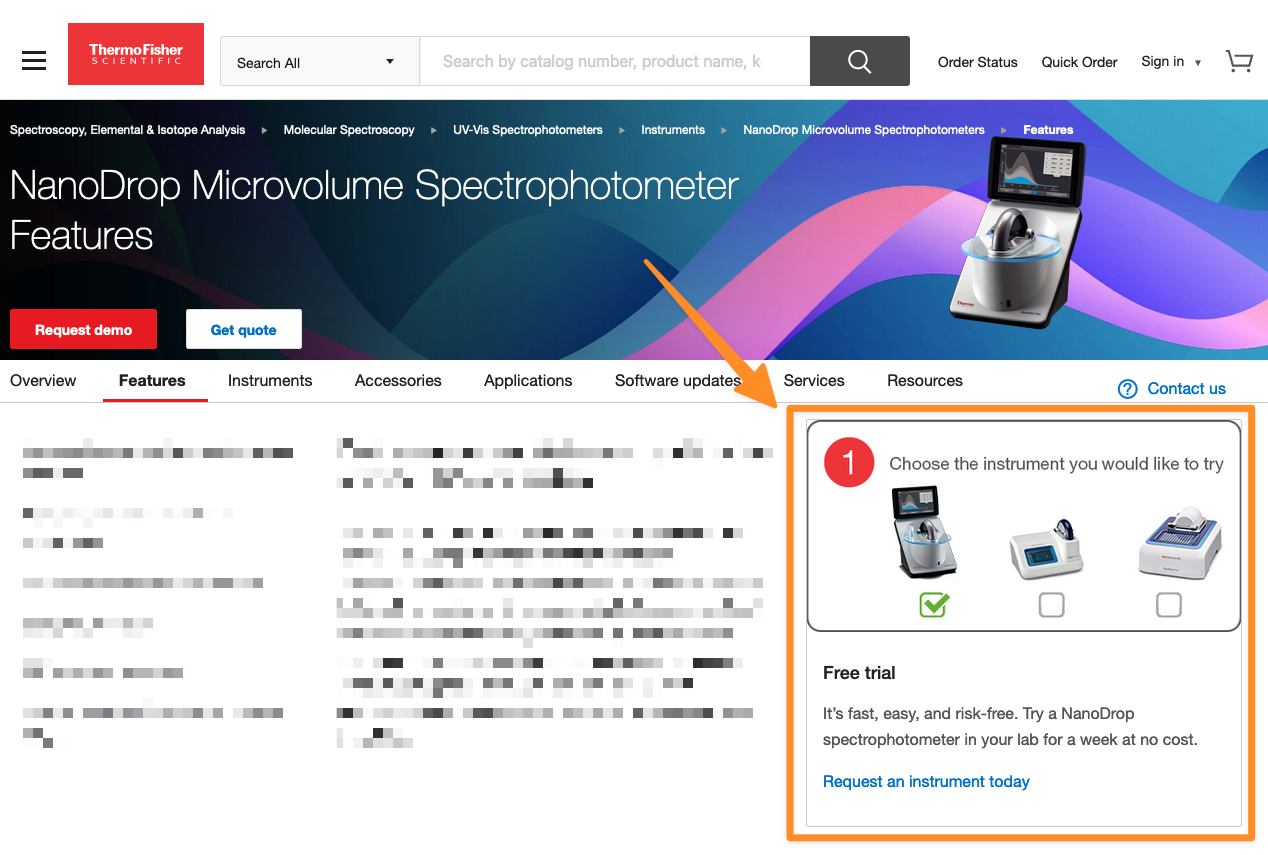

Another way to reduce the perceived risk is to offer a free trial.

This also works in the scientific world, as this example on the Thermo Fisher website shows:

By offering a one-week risk-free lab equipment trial, the company eliminates the risk associated with buying new lab equipment.

Smart move, right?

So remember, play up the wins and play down the potential losses-it's a surefire way to keep your customers happy and coming back for more

7. Belief Bias

Overpromising isn't a good idea, especially when it comes to marketing to scientists.

People are turned off by claims that seem unrealistic or far-fetched, and this is due to the belief bias.

Now, this belief bias isn't just about what we believe - it's also about what we refuse to believe.

Take athletes, for example.

On May 6, 1954, Roger Bannister shattered the myth by running a mile in less than four minutes.

Up until then, people were convinced it couldn't be done.

But guess what?

Once Bannister proved them wrong, suddenly everyone was running sub-four-minute miles.

46 days after Bannister’s performance, John Landy broke a new record.

A year later, three runners broke the four-minute barrier in the same race.

Today, thousands of runners have broken the four-minute mile.

Now consider another example of why overpromising is not good for your brand: Theranos.

For years, Elizabeth Holmes was the rising star of Silicon Valley, claiming her blood-testing tech could do the impossible - 200 tests from a single drop of blood.

But when real scientists started looking into it, the company quickly went bust, and now Holmes is serving an 11-year prison sentence on four counts of defrauding investors.

When it comes to marketing to scientists, you have to play it straight.

These folks are sharp-they'll sniff out any BS in your claims faster than you can say "peer review."

Biotech companies love using words like "revolutionary" and "groundbreaking" everywhere, but once you’ve seen those words a hundred times on every website, they become just a reason to close the tab.

If you want to stand out, explain exactly what your product does and why it’s different from the competition.

Look at the homepage of AI startup Cradle:

It's clean, clear, and you don't see those damn "groundbreaking" hyperbole anywhere.

An example that many companies should follow.

8. Mere exposure effect

The mere exposure effect is simple: the more we see something, the more we come to trust and like it.

Remember that new song you heard on the radio?

First time around, it was like, "Eh, whatever."

But after hearing it a gazillion times, it's suddenly at the top of your playlist.

The discovery of the mere exposure effect comes from psychologist Robert Zajonc, in a paper published in 1968.

In this experiment, participants were asked to read out loud foreign language words over and over again (up to 25 times for some of them) and then rate them on a positivity scale.

Participants were more likely to give a positive score to words they read several times (words repeated 25 times scored the highest), while words they never read had the lowest rank.

And if you think this effect doesn’t affect the brilliant minds of scientists, think again.

Zajonc also showed that the mere exposure can be a subliminal effect that we are not even conscious of.

The mere exposure effect works especially well in advertising, and companies have been using it to sell us their products for decades.

Ever wonder why big brands like Coca-Cola, Apple, or Ikea spend so much on advertising when we all already know them so well?

Because they know that exposure alone is a game changer.

If you are a marketer targeting scientists, the mere exposure effect should be at the top of your priorities.

The simple act of repeatedly putting your brand name in front of them will make them trust you and like your product.

Pharma giants like Bayer are all over this, spending big bucks to make sure their logo steals the show at every convention dinner:

But hey, even if you're not swimming in cash, you can still benefit from the mere exposure effect.

Posting regularly on LinkedIn or launching your own content marketing plan are great ways to use the mere exposure effect to your advantage.

Just keep putting your brand out there, and watch the trust and love roll in.

Thinking, fast and slow

If you're anything like me and you geek out over cognitive biases, then you're probably not surprised to see the names Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky popping up left and right in this article.

Now, if those names don't ring a bell, you may have come across Kahneman's blockbuster book Thinking, Fast and Slow. It's like the bible of behavioral science, packing in decades of research he did with Tversky (who died before the book was published, and before he could receive the Nobel Prize with Kahneman).

In this book, Kahneman breaks down our brains into two modes of thinking: “System 1”, our gut instinct - fast, instinctive, emotional (what we usually associate with the subconscious); and “System 2”, which is our rational mind.

Despite what we like to think, it's System 1 that's pulling the strings behind the scenes, controlling most of our actions.

All of which is to say that I highly recommend reading this book if you want to explore this topic further, as it is truly a goldmine of information and a very surprising deep dive into our minds.